This page give some more insight in the TransforMotivationSystem by giving some examples taken out of the book.. Some of the material is also published on LinkedIn

Marriage & Acquisition: an event and a life together

(July 2018)

What a marriage we had! After a period of hanging out, rumours, some vague pictures, an official announcement and meticulous preparations the Royal Marriage was a fact. The dust has settled down since then, and it’s now up to Harry and Meghan to enjoy their lives together. Because, how magical the wedding might have been, it also was the formal starting point of living a life together. United. Which for most people is one of the primary reasons to get married in the first place.

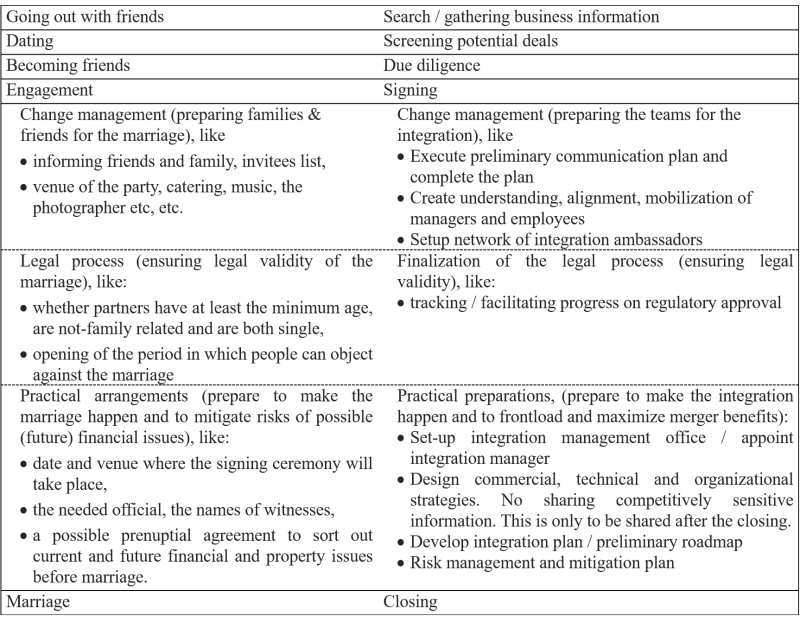

The meeting of other people, the dating, the introduction to the parents, the engagement, the clearance of the registry of citizens, the signatures…quite a process! In fact, it does not seem too far off to see the parallel to business life when organizations come together. There, in the Merger & Acquisition world, one however uses other words like search, due diligence, signing and closing. Another kind of jargon. See below a (vastly simplified) overview of some parallels.

Quite a lot to do between signing and closing. A successful integration after a merger requires thorough preparations to be able to start from Day 1 after the closing with the consummation of the merge. There is no time to lose, given the risk of internal anxiety of managers and employees of both partnering organizations. On top of this, the newly wed couple is not yet up to speed to cope with external threats. For competitors it is a perfect time to attack. To prevent all this, it is important to consider the time between signing and closing as a gift that can be used to build the foundation of the integration (Bain, 2017).

And bear in mind that all these preparations have only one goal: to have a happy, prosperous, royal marriage / merge. In the end it is about neither signing nor closing: it is about the years happily ever after.

Prometheus, probably the first transformation manager

(April 2018)

One of the Greek myths is about the creation of mankind. Zeus, the king of the gods, tasked the titan Prometheus to create man from water and earth. This creation has been given life with the spit of Zeus and the breath of Athena. Zeus did not want man to have too much power and he did not want the mankind to have the knowledge of fire in particular. That is physical fire to give mankind a technical advantage over the rest of the world, but also internal fire of self-consciousness and creativity. The divine fire.

So, Zeus did not allow man fire, because he liked to maintain absolute control over humanity. The fire would make them stronger, just a little bit closer to the gods.

Prometheus however had started to love his creation and stole the fire from the gods and gave it to mankind.

If you would allow me to make an analogy to how a business transformation program is perceived. A transformation manager is tasked to shape the transformation program which is needed to make a strategy work. This craftwork is then brought to life by the executive committee, actively endorsing the needed governance, activities and projects. The CEO personally empowers the transformation manager, and ideally appoints him or her as chief transformation officer. A direct report, as the executive committee members. A titan, not a god.

In the transformation journey, this titan is the go-between, the pivot between the employees (making the transformation happen) and top-management (tasked to set the strategy). To enable the employees to execute this transformation effectively, they need to be given the fire: means, time, processes, room for creativity, training and support. This fire must be given by the CEO and top-managers. And after a while, the fire cannot be taken back: the organisation will have started to work differently, the fire being ingrained in the new way of working. The transformation will be happen, and the organization will have moved on to new grounds. It will have been evolved into an agile organization, empowered by the fire.

There is a difference with myth of Prometheus, since the fire was given nor endorsed: it was stolen. This infuriated Zeus, who punished Prometheus by locking him to a stone, and have an eagle come to eat his liver out. Prometheus, being immortal, would heal in a day, so the next day, the eagle would come back to eat his liver again. And the day after. Until eternity (well, until he was rescued by Hercules, but that’s another story).

A punishment worthy of a good, Greek myth.

On this last part, personally, I would not prefer to make the analogy to a transformation manager. But it is a tricky role, a balancing act between endorsement and support from the top-management and the credibility from the workforce. It is like the transformation itself: playing with fire. Risky, but fascinating for all actors and very rewarding for them as well as for the organization.

From change management to auto-transformation

(February 2018)

Not so very long ago, organizational change was quite structured:

- Every 3 to 5 years, a strategic plan was made

- A transformation program was set up to execute this strategy

- Change management was part of this program to prepare and support individuals, teams and organizations making this organizational change

Since all 3 activities were punctual and on top of business as usual, organizations preferred temporary support by external consultants. In this way the lack of knowhow, experience and man-power could be corrected to pull off these activities. The organization was to contribute to the planning and then execute the plans by following the manuals and so to make happen the strategy.

This has been working just fine in a fairly stable, predictable environment. Strategy was a multi-year plan to reach the goals as set. Part of the strategic process is an analysis of the external environment (customers, competitors, technology, regulation, geo-politics, etcetera). However, given the current pace of developments in the environment around us, the outcome of this analysis is quickly outdated. Which is why the planning process should be continuous (and not every 3-or-so-year), and the resulting strategy should be emergent. Like a rolling forecast, as compared to a yearly budget cycle.

change management as we know it, is no more

Emergent strategies call for continuous transformation. Where in the old days, transformation was a temporary phase, it now is to be part of day to day life in an organization. Consequently, change management as we know it, is no more. McKinsey (2014) prefers to speak of change platforms instead of change management. For instance, because ‘managed’ has moved to ‘organic’: Psychologist Kurt Lewin’s seminal “unfreeze-change-freeze” model still guides how most leaders think about change. But in a world that’s relentlessly evolving, anything that is frozen soon becomes irrelevant.

That’s why most change programs are, in fact, catch-up programs. Transformation or not: it should have been done anyway. Change management should be (part of) management, and management is change management, as Robert Shaffer argues in the HBR in 2017.

However, many organizations have not yet embedded change management or leadership in the fabric of their managers and employees. And this in fact is not only applicable to established organizations which want to gain agility, where most of the change management efforts are focused on. It also applies to the myriad of start-ups which might be helped with a bit more structure to enable them to scale up. Which is not so obvious; like tribal groups, these start-ups must be motivated to give up their freedom to the authority of a more established organisation[i]. This can be access to more resources, but also recognition plays an important role.

Both types of organization would be helped to change themselves into more hybrid models. The table below gives some examples of possible attributes.

[i] Inspired by Francis Fukuyama (2011). The Origins of Political Order”, New York, FSG, p. 89

Organizations are to move to a dual organization model, in which project organization works in symbiosis with the hierarchical organization. Whether they come from an established organisation which has to accelerate, or from a start-up which needs to structure itself. Either way, the glue in this process will be is the people all over the organization who are the ones who make the transformation happen. Their transformation. Usually this transformation is not a core activity for most of the people, so they have to be supported in this process (managers as well as employees). A change program (or platform) should support them in a way so that they do not see the change as a threat but as a challenge. Not as something bad but as something good.

Exciting in a good way.

With the support of this program, people will develop and with it the way things are done in the organization will change in time too. After a while, the extrinsic efforts will not be needed anymore, but have been converted into intrinsic motivation. This is when the organization has really transformed itself. Not only in doing, but also in being. As Kotter states: the DNA of the organization has changed, enabling a continuous transformation.

Endogenous. Auto-transformation.

Transformation maturity assessment - a no-man's land

(December 2017)

Between a furiously designed transformation plan and its actual execution lies a no-man’s land which all too often is neglected in transformation journeys. Despite the fact that this passage can make or break a transformation program. In this article I will explain where this gap comes from and illustrate why it should be addressed before rolling out execution.

In order to simplify the things which have to be done in designing a transformation program, it is helpful to make use of a simple structure. This structure should guarantee that projects do contribute to the overall benefit of the company in a managed way. A very helpful one is the method as developed by PMI (Project Management Institute). PMI has a proven track record and is the world class standard in project management. The pyramid they propose works, and is universally applicable for any transformation.

The sense of the transformation, the Why, is given at the highest level of this pyramid. Starting from this level, the pyramid is increasingly detailed out to ultimately define the What: what are the actions to take, what are the measures to monitor them and what is the desired level of performance.

From a change management perspective, the change model of Kotter is less focused on the structure, but effective in assessing the way transformation is to be conducted. Of course, every organization and every transformation program is unique, but the change model does provide some lessons learned which can only be helpful.

The change model is coherent with the transformation project pyramid and completes the approach with subsequent steps. The figure below illustrates these steps, which are added to the initial transformation pyramid as an inverse pyramid: the execution and the phase in which the change is secured (with a dashboard like the Balanced Score Card and the embedding of the changes into the organizational culture).

Looking at the figure above, the passage from phase 2 to phase 3 is a game-changer: the first two phases are relatively theoretical, and at a safe, abstract level. Analysis does not hurt, and can continue for ages. The actual change will come in phase 3, when it is about making it happen. This is the typical moment of truth, when many organizations realize that they are not yet ready for the proposed change. They are simply not ready to make it happen.

So although this model is well balanced and complete, there is a natural cut-off between phase 2 (defining what ought to be done) and phase 3 (actually doing it). There will be a change of environment and spirit just after the projects have been defined. This is the no-man’s land, empty but full of mines. This is the moment when the antagonists of change will try to sabotage the process: nothing concrete has been delivered yet, so the analyses and concepts are open for debate. Convincing is hard at this point, since arguments are rarely proven yet. Discussions now move to persuasion, in which (top) management should show that they do believe in the transformation program. The truth of the chosen approach and projects will only be proven by the results which will come later.

In this rite of passage of a transformation program, it is helpful to make a transformation maturity assessment. How ready is the organization to go for the next step? What are the reasons why the organization is possibly not ready yet to go for the ‘Make-it-happen’ step? In this way the somewhat intuitive observations can be made more objective, and translated into relevant actions. It is in fact a simplified version of a risk management process. Simplified is important at this stage, since this again is a moment where the antagonists might steer towards the (safe) debate on the method, and by this avoid the key messages on which one has to act. In this kind of process, it is not a matter of being academically right, but about steering to a right decision which needs to be taken. Here, speed trumps conviction.

In the figure below some typical examples are given of situations that a transformation program might be in, and the consequent actions to be taken to overcome the problems.

The actions proposed above have now to be taken first, before the transformation program can continue in an effective way. And continue in a way that there can be sufficient buy-in of the whole organization. Or at least less possibilities for sabotaging the transformation by the antagonists. In fact, these are the conditions which first have to be met before going to the next phase: without these, the organization is simply not ready yet to absorb the changes, let alone making them happen.

So even though the sense of urgency is created, the mission and vision are set, the guiding coalition is ready, and the set of projects are defined — the organization is not ready. Neither for change nor to support the transformation program. The organization as well as the people simply do not know transformation. Most of the employees and managers will have no notion of what is expected of them and why. A large majority of them have been comfortable with the existing organisation, still experiencing strong links with the foregone more stable environment. The autonomy and the way one cooperates is, however, to be changed now. The figure above also gives examples of actions needed in the area of supporting the people in this whole process, focusing on the individual employee and manager.

Taking this observation back to the change model, an intermediate step should be introduced. An intermediate step which is needed to better prepare the organization for the transformation. This extra step serves as a pause in the transformation process, needed to not only remove barriers blocking the program but also to create processes and support to enable the transformation process to take off.

In the figure below some typical examples are given of actions to be taken in this intermediate phase.

These mitigating actions should be translated into projects to be included in the transformation project portfolio, where they serve as the fundamental for all other projects. These projects are the most urgent ones, and the roadmap should be adapted to prioritize these particular projects (which might not have been defined in an earlier stage yet).

This intermediary phase is needed to prepare the organization for the execution of the transformation. Not by exchanging cool slideware at generous off-sites, but to enable the organization to transform the hardware and the software of the organization.

To make it an everyone’s transformation.

True partnerships imply pay-per-customer contracts

(December 2017)

Many companies now strive to improve customer experience. Not as charity, but to improve the inflow of new customers (word of mouth recommendations) and to stretch customer retention. The idea is that the longer the customer stays with you, the higher the value of the customer is. Even though this customer value is not a financial asset on the balance sheet, it is the key denominator of the value of a company. Expected future cashflow defines the value of the company.

Make-or-buy is used to allow a company to focus on their key competencies (make) and outsource the adjacent ones(buy). Instead of trying to also be the best in these activities, you buy the service from a specialized company.

However: the fact you outsource activities, does not imply the contact with the outsourcers is about a price per activity. That creates a contradictory situation: the company want to lower the activities, whereas the outsource partner has a drive to expand the activities.

The only way to combine customer experience, is to create drivers for the outsource partner to sustainably enlarge the (valuable) customer base. It would be time to translate customer experience into the contracts by introducing a pay-per-customer model. The better the outsourcer performs, the better it is for the customer, and with it for the company, and the better it should be for the outsourcer.

Win-win: that’s where partnerships are about.

Timing is the T of Transformation

(November 2017)

As HBR confirmed again lately: corporate transformations still have a miserable success rate, even though scholars and consultants have significantly improved our understanding of how they work. Studies consistently report that about three-quarters of change efforts flop—either they fail to deliver the anticipated benefits, or they are abandoned entirely.

Besides flawed implementation, misdiagnosis is to be blamed for such failures, HBR argues that often organizations pursue the wrong changes—especially in complex and fast-moving environments, where decisions about what to transform can be hasty or misguided.

In my experience, a strategic sanity check is indeed one of the first things to do before sailing away on a course which is not the one fit to the organization. It very often is not the right course for the right organization at the right time.

Even when the strategy did make perfect sense at the launch of a transformation, along the way the course needs to be changed. Adapted to the changed circumstances, as a GPS adapts its suggested route to the changing traffic conditions.

It is the adaptability of this GPS that supports the journey. It should give you a new strategy when the old one does not seem feasible anymore to reach the goals as set. However, it should not change too often – the GPS would be deleted and probably replaced by a new GPS - but with enough dynamics to adapt effectively to the changed environment.

If we see strategy as GPS for the organization during the transformation journey, equally adaptation is part of the game here too. Changes can be triggered by unanticipated moves of the competition, but the radar should cover a bigger part of the environment. It can sometimes be better to wait for national elections to take place, before certain strategic initiatives should be launched. And when the dust has settled down after the elections, you might only have a limited timeframe in which these should be delivered. It might be wise to postpone the validation of the targets of the transformation program after the closing of the regular budget cycle. Sometimes it is better to start preparing the HR department to enable them to support the rest of the organization during the transformation.

Changes in the environment (external as well as internal) will need to be translated in adaptations of the transformation program. Not only to avoid painful and costly waste of energy, but foremost to leverage from a changed situation. Successful transformations ride the waves of changes of the environment. No waves, no glory.

You have to strike when the iron is hot. Even if you’re not fully prepared, or not 100% sure about the consequences. If you don’t adapt the timing, the iron won’t be as hot anymore and all brilliant diagnosis and execution will deliver average transformations.

Beyond the Voice-Of-the-Customer: from KPI to action

(October 2017)

Surfing on the waves of the customer experience hype, many companies have put in place a measurement system to track the customers perception. Frequently, a KPI representing the customer satisfaction has a prominent place on the company dashboard, and is used to set the targets for managers and employees of the company. In this way the employees will be rewarded when the KPI improves, which will trigger a more customer centric behaviour.

So far so good.

However, there is a catch. There is normally more than one customer, and it’s not that obvious to find The voice of The customer. What is The perception of The customer? What do we do with the individual particularities of the different customers? And, given all these questions, what would be a good target to aim for? Best in class? Which class?

To ensure a good proxy of the Voice of the customer, one needs to set-up processes to systematically capture the customers’ voice. Systematic, since we are speaking of a need of continuous flow of information to feed the organization. The environment is changing every day, and the information we need to manage and steer the organization, can consequently not be of a one-shot nature. It imperatively is a continuous flow of information, relevant (which includes: non-biased), complete and timely. The aspect of relevance is also referring to the usability: some information might be very interesting, but is very hard to translate into operational action. So, if we for instance have a customer in a restaurant, telling us that he will rate us a 4 for a cupcake (on a 5-points scale), what does this tell the cook in the kitchen who prepares the desserts? Well, perhaps that we are doing better as compared to the last note received, but why? The cook uses other metrics to measure his processes, and he would be helped if the customer’s opinion could be translated into observations which correlate with his operational metrics. If the quality is a 4, what does this mean for the crustiness of the crust? Is the colour dark enough? Or is it the waiter? This information would help him to translate into operational information (for instance the temperature of the oven). Only that kind of information can trigger a targeted improvement action. The 4 doesn’t do anything.

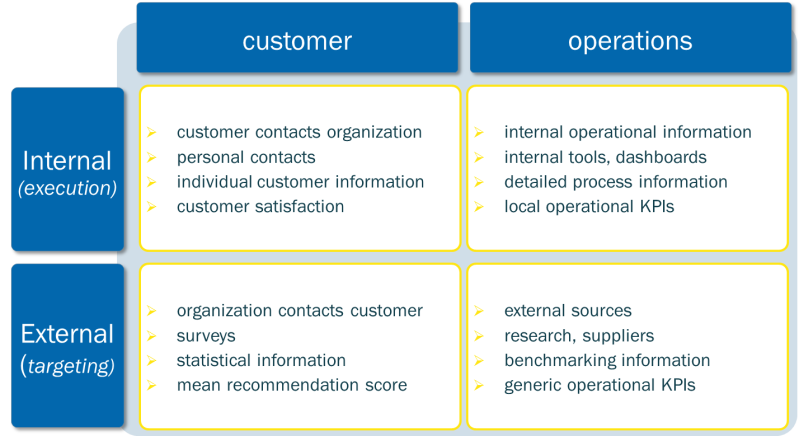

It is not easy, if not impossible (and expensive), to find one information source capturing all aspects of the above required information. On the other hand, we do know there is an abundance of data available in an organization. We just need to choose the correct sources, and then combine the data obtained to create the correct information.

A key source is ‘the customer’: not only existing customers and prospects, but also customers who are being served by the competition, and even customers in other industries. These different types have different traits. First of all, the origin is different: either it is the customer who contacts the organisation, or it is the other way around. The type of information is different too. In the first case these are individual contacts, in which the subject is an individual, specific issue of a customer. In the second case, the information comes from surveys: the ‘source’ is anonymous, and via a grid of questions, statistical valid generic information is obtained. Valid, but generic, so not too practical to translate into action.

So what?

To make this very true information actionable, more is needed: the Voice Of Operations. The language which is being spoken and understood ‘under the hood’ of the organization. As with the voice of the customer, the internal information is used to improve execution, and the external view is useful for thinking out of the box, being inspired by others and eventually for the setting of targets. The external information is generic, as are the KPIs used, which makes benchmarking possible.

When the four different types of information are considered, there is normally an abundance of internal information: a lot of measurements, tons of KPIs and available with a very high frequency. Furthermore, this information is considering various process steps, sometimes to the level of individual customers, and is not statistically constructed out of samples.

In the case that one can correlate the operational data with the customer data, a vast opportunity arises: both sources are complementary. Customer data is very true and relevant, but fragmented and biased by nature. This bias comes from the fact that not all customers react on surveys, or do contact customer service. Furthermore, the information available does not equally cover the whole customer lifetime: customers tend to contact the company more frequently in the beginning of the service, but much less later on. On top of this, the information can be less accurate, since the product of a human exchange between a customer (who is not an expert), and an expert of the company (who interprets the customer’s perception and translate into an operational question). So: although the information is very relevant for an individual customer, in order to multiply its internal usability, it has to be corrected for the bias, the missing data-elements, and the accuracy.

Operational data, on the contrary, might be less relevant from a customer perspective, but is available with a much higher density, completeness and accuracy. But don't let you blind yourself by the abundance: think before you crunch! The fact there is a sea of data, does not mean crunching it will give you sensible information.

If we would put this a bit blunt:

- customer data makes sense, but there is not lot of it,

- operational data is abundantly available, but does not make much sense.

The art of a sensible analysis, is to correlate the customer data with this operational data. When this correlation is established, one can take the next step: to use the operational data as a proxy for the customer data. In this way, the operational dashboard can be populated with Customer Performance Indicators which do guide operations at delivering customer value. What in the end is needed is information about the impact on customer experience if the company changed something in the way it does things.

Because it’s about the journey, not about the target.

TransforMotivation - Motivation first, transformation second

(June 6, 2017, and taken out of TransforMotivation)

Transformation is a great word. It promises action, movement, new dynamics. But it never seems quite clear what people mean by it when using such a powerful word. It is indeed a word with various meanings, and even Google seems to be struggling with it. Typing ‘transformation’ gives you a lot of mathematical explanations and formulas. It also gives references to consultants’ services; all the big names are represented. But most of all Google gives you pictures of people who have lost a lot of weight and now look slim and incredibly healthy. All three types of hits occur on the first page of search results, and the key messages of transformation seem to be clear: it’s complex, you need a consultant to help you, it’s pretty radical, and afterwards you’ll be in great shape.

All good. Which organization would not want that?

A pity that at least 7 out of 10 of these transformation programs fail. We all know that. What we do not all know, is why they fail.

There are several reasons why so many programs have proven not to be effective. Normally one is quite good in doing the analysis and making the plan: the strategy is built upon the vision, which is linked to the mission of the organization.

One has a plan.

But this plan, brilliant as it may be, is only part of the picture. The plan has to be executed in order to deliver the results. This execution, this transformation, is a skill the organization has to master, and has to be done by the people. Managers as well as employees. The key success factor of transformation is the people of the organization, giving the best of themselves to achieve ambitious results, doing something they are not used to doing.

But how can this be done? What drives people? Give children a ball, and everywhere on the globe, they will start kicking it. Most adults would do the same. Why? Because… Something drives people which is hard to translate into technical requirements. Play. Joy. Passion.

Would it not be great to motivate people to transform an organization, to get them enjoying the journey of transformation? To trigger the enablers to release the fun to transform? To find a way to change from a push-transformation to a pull-transformation? To move from artificial to natural? To get a grip on these questions, it seems good to go one step beyond. What is motivating people in the first place? Are there common motivation-drivers which can be stimulated? And if so, how can they be integrated in a transformation program?

The clues for answers on these questions can be found exploring psychological theories, since psychology is the study of the mind and behaviour. Classically the object of psychology is the human being, but this can be taken one step further. This can be done when we follow the powerful metaphor Gareth Morgan has developed for organizations: organizations can be seen as organisms.[i] Organizations seem to develop and react as living beings, always adapting and changing. All too often seemingly having their own way, having their own character. Taking this metaphor further, one can apply psychological models on transformation as well. If one looks at motivation of the individual employees, it seems logical to consider the motivation of a team of people as well. The step from there on is not too far-reaching, to also look at the drivers of a motivated organization.

[i] Morgan, G. (1997). Images of Organisation. Thousand Oaks: Sage publications, pp. 33-71.

Wearing a shirt of Messi, does not make you a Messi

(June 12, 2017, and taken out of TransforMotivation)

The business model of football has changed. Clubs are transforming from pools of local talents, financed by the canteen and entry fees into organizations which make money with TV rights and retail, merchandizing and licencing (the last category has tripled between 2014 and 2016 at Manchester United up to 100m GBP. As an example). The Barcelona brand is valued over $ 3.5 billion. Times have changed. Things have transformed. Who would have thought that now so many people believe that putting on a shirt of Messi will suddenly transform them into a better football player?

Transformation is not a day-to-day evolution, it is not an incremental change. Transformation implies a rupture, sometimes a radical change. This will not only impact processes, tools and the organization, but foremost the people. For employees as well as managers, a transformation program will mean changes for them. Changes which are not only to be observed, but which have to be carried by the employees and managers. They are the actors who make the transformation happen.

Given the fact that the outcome of transformation is not really known at the start, and that the processes of transformation will have to be adapted in time, it is not normally that obvious to onboard people on this journey of uncertainties. It is not easy to motivate people to join in this adventure.

In former times when things were more predictable, sharing the company’s Northern Star with the employees might have worked to motivate them. A clear, common goal. A red thread which can be consistently communicated, which is recognizable for all employees, and with this collectively motivating the employees to go for it. But… those were the days… Nowadays the future surrounding organizations is not that clear. Not precise. It is just too dynamic. Full of uncertainties.

Because of these uncertainties, in a transformation process it is better to emphasize the journey, and not the end goal. A collective journey, but with diverging and changing roles for every individual. An organizational journey which respects the individual contributions and roles, which should take into account the motivation of the employees.

The Collective Carrot will not work anymore to win the hearts and heads of all employees and to guide and train the hand of the organization. In fact, this Overall Goal has the power to confuse the head, to stress the hand and to break hearts. No, a transformation program has to fit with and be attractive for the individual actors too: transformation can only work with employees who are motivated to join the journey.

Motivation can be defined as ‘a reason for acting or behaving in a particular way’ and can be divided into three factors:

- purpose

- autonomy

- mastery

In the following posts these three factors will be explored more, but then from the perspective of transformation.

The aim of transformation is to transform. It is only a means to get to the results. In order to ensure a lasting stance, one should at all times bear in mind which results one is trying to achieve with a transformation activity. And since transformation is embedded in an existing organization, it is a prerequisite to obtain the needed support of this organization to be successful. Sustainably.

Like becoming a better football player, transforming an organization can only work if you believe in it, you work hard and you develop your talents. It has to come from you, from the individual as essential part of the organization. From the heart. It is not about putting on a Messi shirt.

Plans are worthless, planning is everything

(June 19, 2017, and taken out of TransforMotivation)

The first motivation factor, purpose is about the why of transformation. Why do we need to transform? Why am I implicated? How is my project contributing to the overall story? And how do I find my personal value-add back in the overall journey? This is about giving sense to individual contributions to the overall transformation. This factor is about reasoning, about the brain. This is about the head.

In the figure below the motivation factor purpose is laid out in three layers.

The first layer is geared to the results one is aiming for. These goals are to be defined by the stakeholders of the organization. They are the ones who define the purpose of the organization itself which is to be transformed. The first step is to identify the various stakeholders, after which their expectations can be found which will define the results to be achieved.

The second layer is integrated in most running transformation programs: the strategy of the organization. This is where the action of the organization is articulated, defining the steps to be taken to proceed in a way that the vision is respected and the competition is beaten. In this layer, the purpose of the organization is translated via the strategy into concrete action plans. A common pitfall here is to come with an off-the-shelf set of projects, neglecting the organization which is to be transformed. But strategy is governed from the existing situation, and not from the alleged end state. If this element is not properly taking into consideration, the strategy is disconnected from the organization, and will subsequently fail. Furthermore, the plans should fit into the most probably already running initiatives or programs in the organization. Transformation never starts from scratch.

The last layer is the one which is needed to support the first two layers. In order to deliver the results, a plan is defined to get there. This plan, this strategy, is to be accompanied by an approach which fits the organization. One has to define the way this program will be done. If we take one example, Samsung has a different way of doing things than Apple. Samsung has a different corporate culture than Apple, which consequently means a transformation program will be designed and executed differently. The Samsung way is not the Apple way. On top of this, the Apple way in 2017 is not the Apple way of 2007: Apple has changed over time, and with it the Apple way of doing.

In order to work respecting the way things are done in the organization, and to create understanding of the fact that this transformation is contribution to the whole organization, communication is very important. Transformation is by definition different from business-as-usual. It means working different-as-usual. It aims to change the usual activities and with this the culture of the organization too. To avoid confusion in the organization, it is advisable to create a distinct identity for the transformation program. The program should be clearly recognizable for everyone, so that the activities make clear sense in the right context. It should be branded. The branded transformation program enables consistent and effective internal communication.

People need to know why this transformation program takes place and what the progress is, how it relates to the existing organization and the people themselves. This understanding is key to nourishing the motivation factor purpose of the individual employees, as well as of the organization itself.

Ceteris paribus does not exist in real life

(June 26, 2017, and taken out of TransforMotivation)

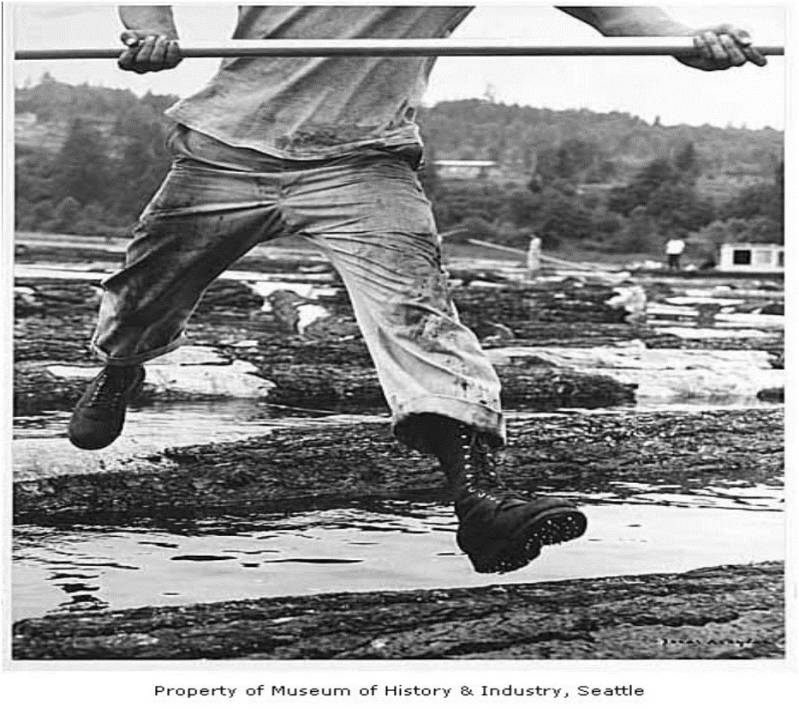

As described above, we now have addressed the motivation factor purpose, which means the easy part starts. The thinking has been done, now it’s just about execution. However, ‘Ceteris Paribus’ does not exist in real life: various (if not all) parameters are changing all the time, so how would a meticulously detailed transformation plan work out in the open? Transformation has become more like crossing a river, jumping from tree trunk to tree trunk: the path has to be adjusted all the time, even though the goal (the other side of the river) remains as it is. It is now about looking ahead (‘are we heading for the other side?’), but in combination with looking right in front and around you for possible new steps to be taken (‘which tree-trunk will I jump to next?’).

The second motivation factor, autonomy, is related to the ways transformation can be organized and how it fits into the existing organization.

Autonomy is the motivation factor which has to do with the elements of being able to take initiative, to have the liberty to do the things you think you should do. It is about creating the space to develop, to test things, to enable creativity to thrive. This autonomy does not need however to lead to a solitary situation: in fact, it is all too often the contrary. People tend to flourish working in a team, able to leverage from the experiences and knowledge of others. This has to do with people surrounding you who enable you to stretch even more. To go the extra mile. This is also part of autonomy, be it on the other side of the spectrum. Together being stronger, but at the same time enabling the individuals to excel.

People are different, teams are different, so autonomy has many faces. And organizations which seek transformation are of a very diverse nature. Formulated otherwise: there is no One organization. In fact, most organizations are more a federation of culturally differing organizations. This has a critical effect on the way a transformation program is managed, since not all of the entities, not all of the employees are in the same situation, in the same state of mind. That is: some of them are more ready or more open for change then others. Others might need a bit more time to get there. A third category covers the ones who are tired of all the changes they have gone through last years and are now reluctant to change. And of course the ones who just reject change, due to various reasons.

The one-size-fits-all approach will only lead to non-acceptance by the various actors of transformation, and should therefore be avoided. If one on the other hand enables the various actors to adapt the transformation to their natural pace in the cycle of life passages, the energy which will be released will be fantastic. The sky will be the limit.

To leverage from this potential it should be addressed intelligently in an overall transformation program: there is One Transformation Program but it has many faces. The methodology which is to be used to execute the transformation program should on the one hand respect and leverage from the organizational diversity, and on the other hand allow for a harmonized approach. It should allow for creativity but also be manageable.

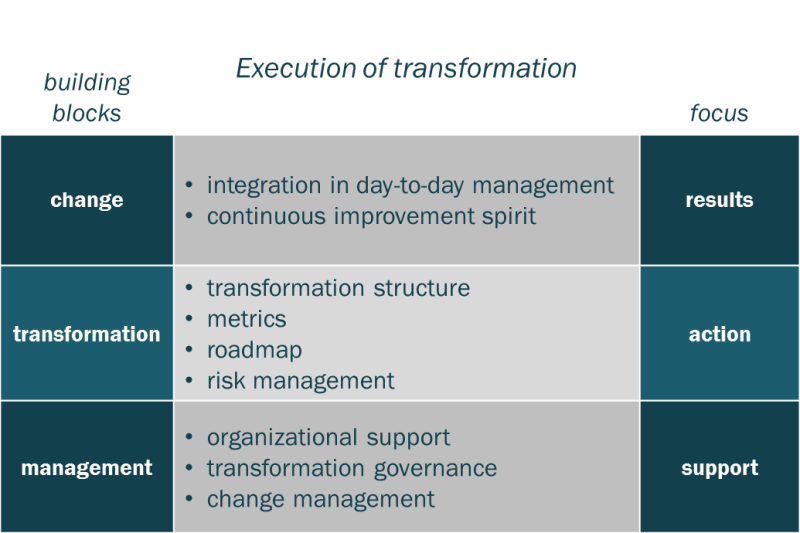

In the figure above this model is illustrated in three layers. The engine is the execution of transformation program. This is where the actual projects, programs and the portfolio are structured, monitored and aligned in a roadmap of projects. This mechanical part of a transformation program is not to be underestimated: it is not only about processes, or an add-on to the existing organization. It also implies radical changes in the way the activities are organized. Other metrics are used.

The transformation program is in need of various functionalities, which are to be supplied by the existing organization. People should be exempted from regular activities to work on the transformation program. The organization should be flexible enough to free up these employees for them to contribute to the projects. And after the contribution is done, the employees have to be absorbed by the organization again.

Besides contributors, other resources can be requested, like management support, assistance in communication, etc. In order to help the existing organization to manage this support as well as other changes which will come during the transformation program, a solid change management program is to be set up.

Another aspect is the transformation governance which should team up with the governance of the existing organization. Since the transformation program is running in parallel to business-as-usual, the decisions taken in transformation have to be respected and confirmed by the existing corporate governance. For a transformation program to be successful, it has to be crystal clear who decides on what and how the organization will support the decisions taken as well as the changes as provoked by the transformation program.

Both the support and the action should be geared towards the results they are to deliver: well managed projects. But well managed projects in themselves are not enough: the projects should be efficiently delivered, and the results of the projects should be implemented in the day-to-day activities. This process of changing and improving the current state, should trigger a spirit for continuous improvement: there is always potential to improve the processes. To reduce waste. To improve the customer experience. Since many of these improvements in fact are minor adjustments of day-to-day operations, they should be at best initiated and managed by operations itself. These small changes might be insignificant in themselves, but usually have a big multiplier: changing one small thing in a highly repetitive process brings significant results. Continuous improvement in a continuously changing world. Transformation is the opposite of ceteris paribus.

Always change a winning team

(July 2, 2017 and taken out of TransforMotivation)

The third motivation factor addresses the heart of transformation the people who make it happen. This factor is about mastery, about how the organization and the people can develop themselves.

Carl Rogers has done groundbreaking work on the motivation of organisms, formulating his ‘actualization theory’, which states that all organisms have a natural, built-in motivation to develop their potential to the fullest extent possible. They all strive for mastery. Since we can see an organization as an organism, this principle can be applied to all organizations: they all strive naturally for mastery.

In the context of transformation, this means organizations, as well as the employees, have an intrinsic motivation for improvement. A good transformation program should enable this built-in motivation to flourish. For this, the actualization theory teaches us that this can happen when we use the natural drive which is in us all. As simple as this seems, ‘just letting it go’ is in reality not that easy. In real life, one has to deal with extrinsic motivation as well.

Any organization has to serve several stakeholders, society, partners, investors, customers and employees. Given the diversity of these stakeholders, there will be a diversity of extrinsic motivation factors as well.

What often is observed is the risk that an organization is forcing itself to ‘play the role’ of a company which is loved by shareholders, where its intrinsic drive is different: one tries to be the Ideal Self, another persona. When taken too far, this will lead to a state of psychosis, which can lead to a vicious cycle of de-motivation. Operating companies, as well as employees, will experience fear for the unknown and the company will be blocked by anxiety, which will lead to sub-optimal action as well as untapped potential.

The above-mentioned risk of getting into a state of psychosis is very present during a transformation program. To avoid this organizational psychosis, it will be the challenge to give the different entities, as well as the employees, as much leverage as possible from their respective natural drives.

In order to liberate the power-from-within, a transformation program has to respect the diversity of the organizational entities, as well as the diversity amongst its employees. This should for instance also be input for the internal mobility strategy of human capital: in case some projects need to be done, we need to match the employee to the project. Personal development and training might mitigate the impact of a mismatch, but it is always better to start off well with proper staffing.

The variety of the roles will enforce the overall team, and every type has its role to play. It is the chemistry, the interaction between various team members which make the project team flourish.

On top of the roles and their interrelationship, there is the dynamics of time. Since a project is inherently changing during the project lifetime, the roles and their relationships should be changing too. This means that ideally the staffing should also change in time, depending on the evolving roles in the project team. Or the program or portfolio team.

Always change a winning team.

After this matchmaking is done, the time has come to invest in the development of the actors: transformation is different from business-as-usual. Training is a good lever to help develop mastery in the new areas of project management, change management, communication, etc.

Mastery is not only about entities or project managers who should be recruited and developed. It is also about helping managers to play their role in project and program management. These managers are the ones who are crucial in the allocation of resources: projects do need manpower and do trigger spending. This has to do with mastering the role of management and leadership. And this includes top management, since experience shows that successful transformation programs have been endorsed actively by top management. They have to go one step beyond management: they have to lead transformation. They are the ones who should win the hearts of the people for transformation, whereas the transformation program itself should win the minds. As Tony Joe White once put it: “I do not know of what you speak, but I do believe in the words you say.” This is a challenge for managers: employees have to believe in what the managers say. And for this the managers themselves have to believe in what they say. It has to be authentic. They have to be intrinsically motivated, and managers have equally to be recruited and developed to enable them to master this important lever to contribute to the success of the program.

Finally, the rewards system has to fit with the new dynamics and stimulate people and operating companies to engage into transformation. Rewards can be linked to salary, but also to non-financial benefits like trainings, like travelling, like personal acknowledgement by top management. If one choses to leave an existing job to start working in a project, it would be stimulating if the contribution to a project is considered as an enriching experience which improves the employability of the employee: the probabilities on promotion should increase for this employee. In this way more talents will be triggered to actively invest themselves in transformation, which is also good for the transformation program itself. For more experienced employees, perhaps less interested in a career-boost, there should also be triggers to stimulate them to engage themselves into the program.

There is an array of possibilities in this field to motivating people to individually engage in the adventure which is called transformation. People will engage themselves, as long as the organization reciprocally engages itself towards the individual too.

Transformation is not a crash diet

(July 7, 2017, and taken out of TransforMotivation)

All three motivation factors mentioned above contribute to the success of a transformation program. And all three of them are important to become successful. All over the organization; transformation is an organizational effort which cannot be delegated to some more or less isolated persons doing the best they can. Furthermore, all activities as presented in earlier posts should be orchestrated properly.

They all are like instruments playing together: it will only work when the timing is perfect. Conducting transformation is a lot about doing the right things, doing them right. But also doing things in the right sequence, and at the right time. Transformation works as a system, in which separate elements mutually interfere with one another. From the start until the very end.

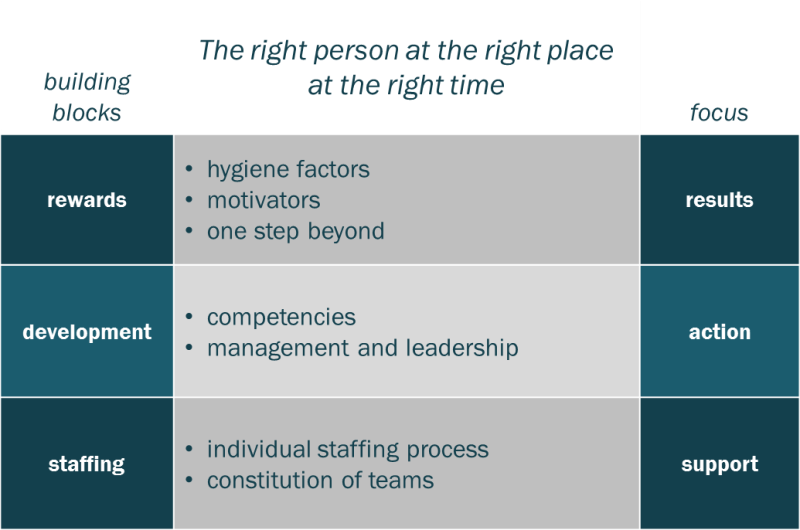

The scope of the transformation program should in certain cases be limited to improving the efficiency of the program, without losing in effectiveness. There is no need to bring in the heavy artillery when a swift action will be enough. In order to adapt the scope of the program to the situation, transformation programs can be seen as modular, built up out of one, two or three modules. These modules, or complementary cycles, are part of the TransforMotivation System, as illustrated below.

The basic transformation cycle can be very short: stakeholders give the direction, which is translated into the strategy and projects. The projects are executed and implemented and the subsequent results serve the stakeholders. In cases where the projects require the involvement of more and diverse entities, the complexity increases and a second cycle is added to the program. This cycle takes the cultural diversity of an organization into consideration: differences between entities as well as between entities and head office. The cultural diversity influences the transformation program in the way it should be run, and sometimes too in the projects to be included in the transformation roadmap. When a transformation program increases in complexity and scope, a third cycle is added. The third cycle covers the involvement of the organization and the mobilization and development of the actors involved in transformation.

Since it depends on the situation how big the transformation program should be, it would be wise to conduct a quick, high level assessment to see how bad things really are (or not), before launching the transformation program. The TransforMotivation System offers a structure to ensure a meaningful but quick assessment by questioning the organisation per building block of the TransforMotivation System.

After all this work, the organization is capable of delivering the changes as initiated by the transformation program. These changes will deliver the results the stakeholders have requested the organization to deliver. After which the transformation program has done its job and can stop. However, in case the results are not sufficient or the stakeholders have changed their minds, the stakeholders might not be satisfied with the transformation. Then a new cycle will be started. A cycle which might lead only to more stretching targets for the existing organization, but perhaps again calls for a complete transformation, since the new expectations require another radical change.

Also for this new episode, the same sequence can be followed, with only a change of parameters to start with. And l’histoire se répète, since the Head, the Hand and the Heart are mobilized. All the elements are there to continue this transformation cycle, as if it was running on its own. This time things will go quicker and better, since the organization has learned from earlier cycles. The transformation will again deliver radical change, but the transformation process will run more smoothly.

However, in the end a nicely zooming transformation machine, well-crafted and perfectly running, is not a goal as such. It is about the results of the projects which will transform the organization. The transformation program is only an enabler to make change happen. It is the bridge to cross the river, and after the crossing the bridge is obsolete. New rivers will appear, and new bridges will have to be crafted. It is this journey, these new discoveries which will deliver the success of an organization. Sustainable success for the organization and for all of its stakeholders, driven from the inside. It is not a crash diet, but the organisation will be in great shape. Sustainably.